For the rest of his life, Webb Kosich ’26 will be indebted to his little sister. Not that she plans to take advantage of that, of course.

“Well,” said Julia, who is a year younger, “I have borrowed his car a bunch of times already.”

It will probably be a while before Webb, a sophomore on the men’s soccer team at William & Mary, even thinks about saying no. Julia’s selfless act six months ago is the reason he is standing as strong as ever.

“Anything she wants,” Webb said. “She was so great about this and willing to do it. She’s the main piece of this story.”

It was Julia who donated her bone marrow to Webb, who had developed a blood disorder that if not properly treated could have led to serious health issues. It was Julia, then a high school senior, who put her life on hold so her older brother could resume his.

“It’s an amazing story,” Tribe coach Chris Norris said. “Hopefully, he continues to trend upward from here and it’ll soon be a distant memory for him.”

Webb was coming off a promising freshman season in which he played in every match and scored two goals. In early January, still home for holiday break, he began noticing some peculiar things. For instance, he was getting really tired after his runs. And midfielders can run all day.

Then, little red dots began surfacing on his legs and arms. He began bruising for no apparent reason. Enough was enough: Webb decided to get checked out at his local hospital in St. Mary’s County, Maryland.

That set the whirlwind in motion. Blood tests showed a lack of platelets, white blood cells and red blood cells, an alarming report to say the least. Doctors weren’t able to narrow down the cause and eventually sent Webb to The Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore.

“I actually went by helicopter,” he said. “I guess I was considered a big enough emergency to get choppered up there. Then, basically, it was a waiting game.”

Webb underwent a bone marrow biopsy, but his doctors remained uncertain. He said they were “preparing me for cancer or leukemia,” but nothing was definitive. Until, eventually, there was a clear diagnosis: aplastic anemia.

By definition, aplastic anemia is a serious blood condition that occurs when bone marrow cannot make enough new blood cells for the body to function properly. Only two out of every one million people in the United States are diagnosed with it each year.

“We had been doing research a couple of days before that, but I had no idea what it was,” Webb said. “I had never heard of it.

“When they broke the news to me, I had mixed emotions. I was happy I didn’t have malignant cancer. But at the same time, I knew I had a long road ahead of me.”

Webb was told he would need a bone marrow transplant. His parents, Jefferson and Jennifer, were immediately tested. So were Julia and their younger brother, Robert. There’s about a 30% chance of finding a match within the family.

Webb was sent back home for three weeks to quarantine. And wait.

“It was a really long process,” he said. “I had to get chemo and radiation, get everything scheduled, and get the insurance stuff worked out.”

About a week later, accompanied by Jennifer, Webb went back to Hopkins for an appointment. And there was news.

“One of my main doctors came over and was like, ‘I’m not supposed to be telling you this yet, but your sister is a 100% match,'” Webb said. “We were freaking out, and he was like ‘Be quiet!’ It was awesome.”

Yes, Julia was a perfect match, which was the best possible news. A 17-year-old high school senior at the time, Julia was understandably a little scared. But she never considered not doing it.

“It was my grandma who sat me down and told me that a year from now, I’d look back and not regret it at all,” said Julia, now a freshman at the University of Tampa. “I feel very lucky we were a 100% match because that’s very uncommon within the family. It was a miracle that I was the one to be able to help it.”

Then again …

“Everybody always mistakes Webb and me for twins, actually,” she said. “Maybe we have more similar genes because we look more alike.”

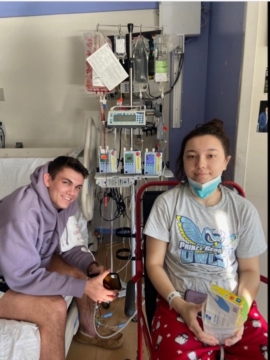

Webb was re-admitted to Hopkins in mid-February. He underwent nine days of chemotherapy and a day of radiation. Then, after a day of rest, came the transplant on March 9.

Bone marrow was taken from the back of Julia’s pelvic bone (she was under anesthesia) and transferred by infusion into Webb’s bloodstream.

“The whole process really happened very quickly” Julia said. “The recovery time for me was probably about two weeks until I could fully go back to school. But compared to what Webb went through, I had it very easy.”

Webb was listed at 5-foot-11, 170 pounds on last season’s roster. In the months since, with chemotherapy hitting hard, his weight dropped as low as 138.

After the transplant, his appetite gradually increased and he was able to keep food down. With regained strength, he began working out. And now, he’s back to 170 pounds.

“I’m feeling like myself again,” Webb said.

Although he is allowed to practice with the team, Webb has not been cleared for contact. And since soccer players tend to crash into each other on the pitch, that means he will be redshirting this fall. He still has three seasons of eligibility remaining.

“I’ve been popping into practice and playing neutral, passing the ball around and doing whatever I can,” he said. “Norris has been good about that by getting me involved with the team. When they’re scrimmaging or something, I usually go off to the side and do some sprints.”

Norris, whose team will hold a Be The Match drive on Sept. 30 when it hosts Drexel, is impressed with how Webb has come back.

“He looks strong and healthy, and I’m sure if he had clearance now he’d be contributing significantly,” Norris said. “But obviously, we have to be very careful for him and heed the doctors’ orders and make sure when he does come back that he’s fully ready.”

It’s been nearly 28 weeks since the transplant. March 9 can be seen as a second birthday, and he’ll never forget it.

“I’m not allowed to get tattoos yet because they could give me an infection,” he said. “But I’m going to get that date tatted on me somewhere.”

He might want to include Julia’s initials.