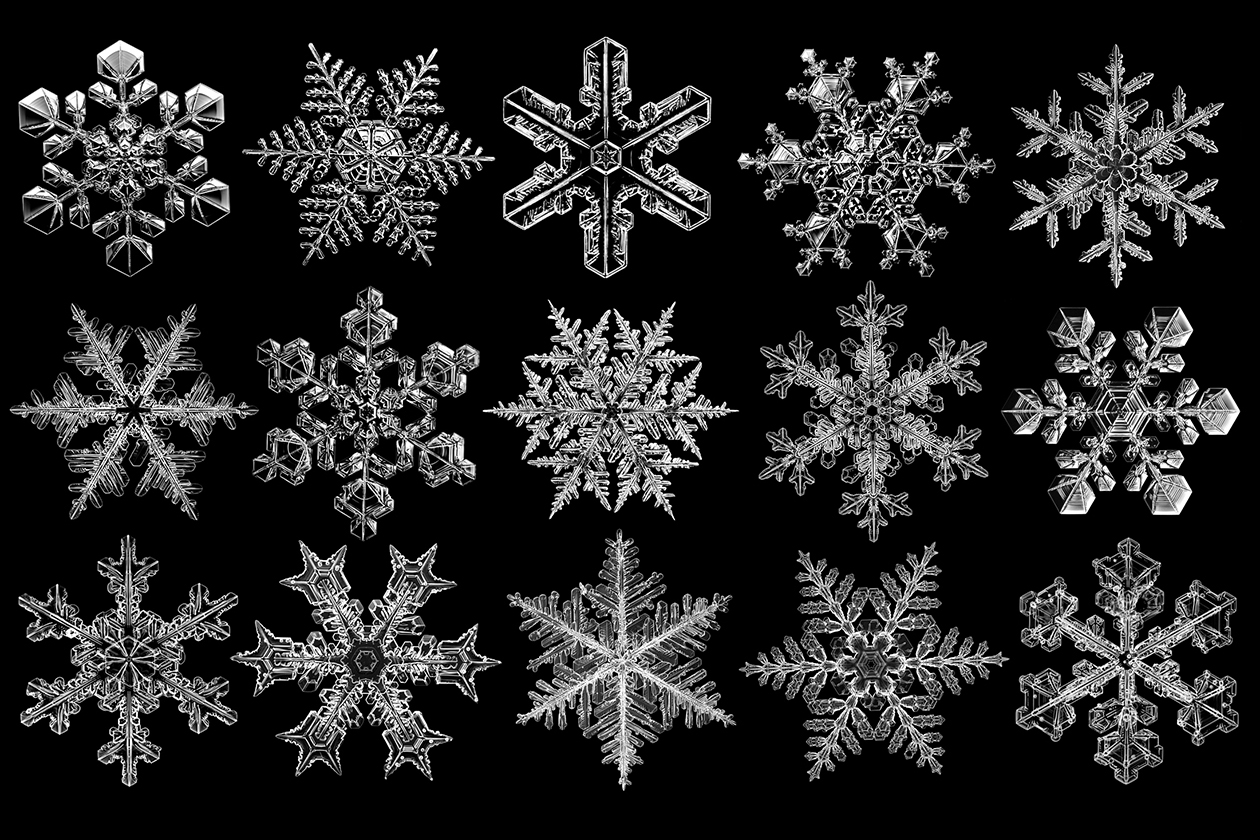

In the iconic “Sound of Music” score, “My Favorite Things,” a young Julie Andrews lists snowflakes as objects that bring her joy. While some people would rather avoid snowflakes and the slippery roads that accompany them, no one can deny the beauty and intricacy captured within these ephemeral shards of ice.

But what gives a snowflake its symmetry? And is it really true that no two snowflakes are alike? William & Mary News pondered these questions with the recent blustery weather and asked two professors for the details. Junping Shi is a professor and interim chair of the William & Mary Math Department. He applies his expertise in partial differential equations to model biological processes. Robert “Bob” Pike is a professor of chemistry at William & Mary and specializes in inorganic chemistry and crystallography.

Questions and answers have been edited for length and clarity.

Q. With unfathomable numbers of snowflakes falling since Earth began, is it mathematically possible that no two are identical?

Junping: Mathematically, it’s not impossible that two snowflakes could be the same — it’s just astronomically unlikely.

A snowflake is formed by adding molecules one layer at a time. Every layer depends on the exact state of the environment at that moment, hinging on thousands of microscopic variables. As a snowflake journeys earthward, it encounters fluctuations in temperature, wind, humidity and pressure, to name a few factors, that shape its unique structure. Because this process is so highly variable, the number of possible snowflake shapes is effectively limitless.

To put it in perspective, a single snowflake contains about a quintillion (10¹⁸) water molecules, and while their structure must obey certain rules, there are many different ways these molecules can come together based on environmental conditions.

Q. Why do snowflakes have six-sided symmetry?

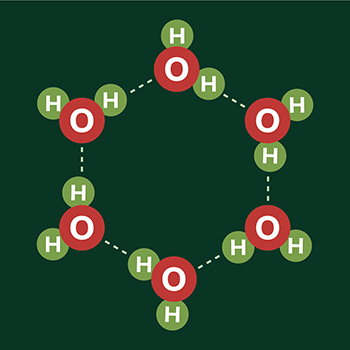

Pike: Snowflakes are crystals — meaning their molecules are arranged in a very ordered, repeating pattern. Nature allows for only seven kinds of crystal systems and one of them is hexagonal, i.e., honeycomb-like, which we see in snowflakes.

This hexagonal pattern comes from the structure of water molecules. Each water molecule is composed of H2O, i.e., two hydrogen atoms attached to one oxygen atom. In ice, the oxygen atoms also form hydrogen bonds with neighboring water molecules. When frozen, these water molecules arrange into a hexagonal lattice.

This organized form is also what gives rise to ice being less dense than water, unlike most molecules.

Q. How is a snowflake formed?

Pike: The beginning of any crystallization is called “nucleation.” It takes a solid surface to induce nucleation. So, in the case of water vapor, nucleation typically takes place on a microscopic fleck of dust in the atmosphere.

The initial ice crystal that forms on the dust particle has six-fold symmetry and must grow in a way that preserves this symmetry. But that single crystal doesn’t keep growing. Rather, it serves as a nucleation point for additional crystallites that form. These crystallites can form at the six points on the hexagon or on the face of the hexagon, which is why some snowflakes look more like six-sided rods vs. virtually flat hexagons.

In the case where new crystallites form on the corners of the hexagon, each arm of the snowflake forms a series of new crystallites, each having its own slightly different growth trajectory. Moreover, the arms can branch, creating new crystallite patterns and producing the intricate spokes and spires of a snowflake.

Even in true single crystals, such as quartz crystals, each crystal usually looks a bit different because the growth rate of the various possible crystal faces is a bit different. This effect is hugely enhanced by the branching in snowflakes.

Q. What factors contribute to the unique design of each snowflake?

Pike: Temperature plays a key role as does humidity. For the snowflake to continue growing, more water particles in the surrounding environment need to choose to crystallize and join the snowflake rather than stay in the vapor state. So, the micro humidity right next to the snowflake is an important factor governing how and where it grows. The path each snowflake takes to the ground, buffeted about by the wind, also impacts its shape as it encounters different particles and microclimates in the air.

Q. Bottom line — should we still tell kids, “No two snowflakes are alike?”

Pike: As I see it, any lack of truthfulness in this statement probably lies in the distinction between the idea of true infinity and the reality of “near infinity.” Kids don’t need to grapple with that distinction!

Catherine Tyson, Communications Specialist